Drawing Dementia

Drawing Dementia

I retired in 2017 and three weeks later my mum, normally a very active octogenarian took seriously ill. She made a recovery of sorts but was then diagnosed with Vascular Dementia which had gone undiagnosed for many years.

This diagnosis plus another of Parkinsonism, a condition which mirrors the outward physical conditions of Parkinson’s disease, marked the beginning of a rapid decline in my mum’s health and cognitive ability. This was also the point at which my role changed from a part-time to a full-time carer. I soon became aware, even after being a single mum of three and balancing a full demanding job, that this was to be the most difficult role I had ever taken on.

As my mother’s condition worsened, we were given a ‘support package’. We had Carers, Social Workers and all sorts of other professionals popping in and out of our lives and our home.

We were thrown into a new world that we didn’t understand and that kept changing. My mum, struggling with her failing health and memory, all these strange new people and regimes down to the most intimate of personal care, all of which seemed imposed on us even though I knew we needed help. It was confusing at best.

I don’t mean to sound negative because we were grateful for all the help we received, but our quiet peaceful and private existence was no longer. Nothing was stable, things could change from one day to the next, carers were taken off while others were put on, times were altered, not helpful when you are already confused and struggling with everyday situations.

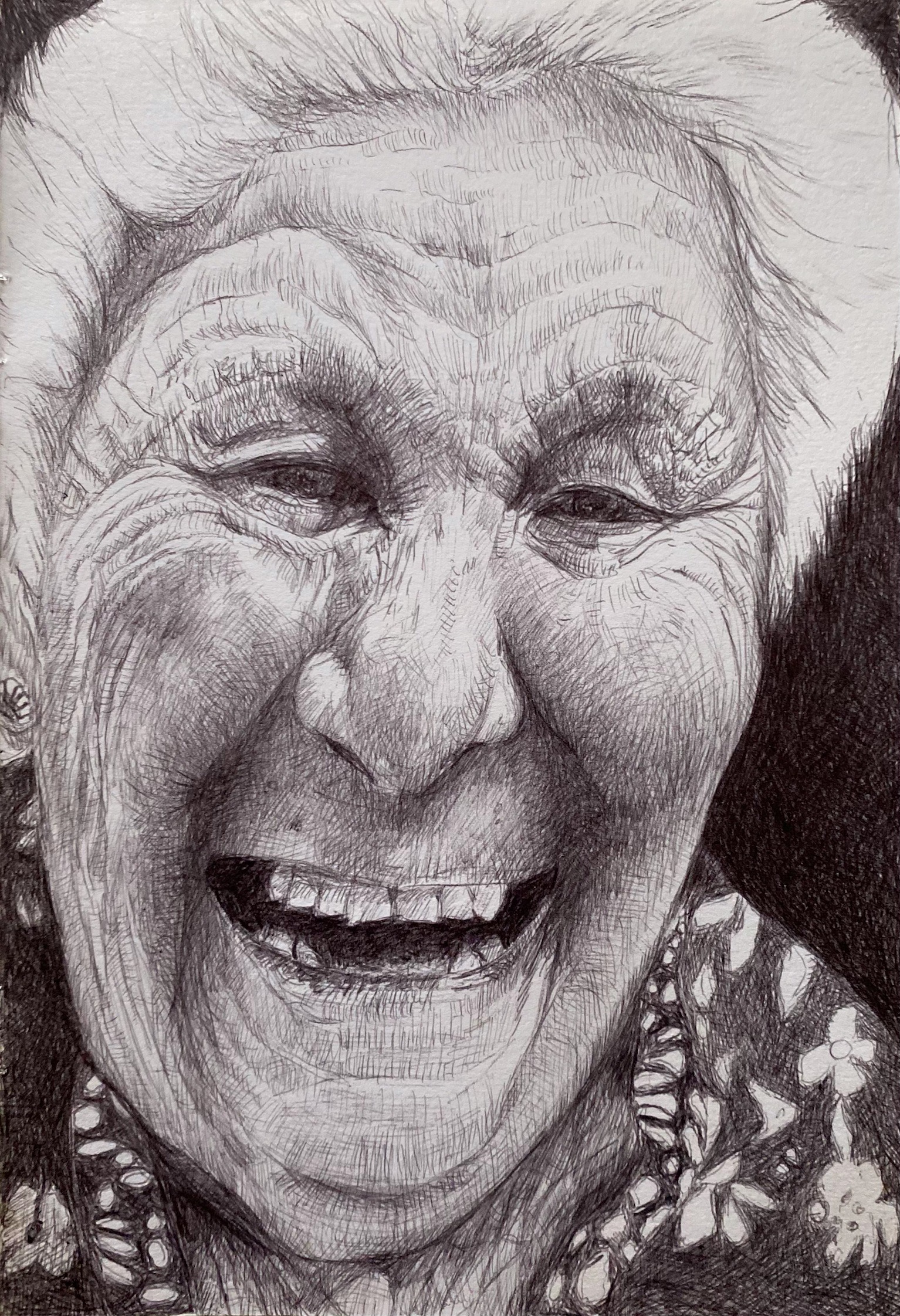

My mum’s condition inevitably worsened, and she was in and out of hospital many times. She went through so many stages of behavioural change that went on for weeks at a time. Singing for hours at the top of her voice, and while it could drive you mad at times, it was funny because I think she thought she could go on stage with this newfound skill.

Then it changed to yelling for hours at a time and I longed for the singing to return. These behaviours lasted for months at a time. She was constantly demanding and wanting attention, calling my name. She didn’t want to be left alone and she had no concept of time and was no longer amused by the TV or calmed by music.

She entered into a stage of delusion which started when she was in the hospital. She saw demons at night on the wards. They were real to her. She described them so vividly but couldn’t bring herself to tell me all of the things they did however she called them ‘pure evil’. “Get me out of here, please, please Margaret get me out of this evil place”.

From then on, she would refuse to go back to that hospital because of what she saw there. It was real, she was living in some kind of hell inside her head, and I couldn’t help her. And then there were monkeys. These monkeys came with her from that same hospital, she explained where they lived on the hospital grounds, bred there by some strange man.

Unfortunately, at least one followed her home and tortured her in her room for weeks, hiding in corners or behind me when I came into the room or looking at us through the window, and she got cross when I wasn’t quick enough to see them before they disappeared. She lived in a dark and frightening place which was so real to her.

I was entitled to two, three hour periods per week, of additional care time to allow me to do whatever I wanted. I went for walks but because of lockdown couldn’t visit friends, go for coffee or to the shops or wander around the museum, like everyone else downtime pleasures were limited. Sometimes I just went and sat in the car at the water’s edge and watched the birds, the boats, the rain.

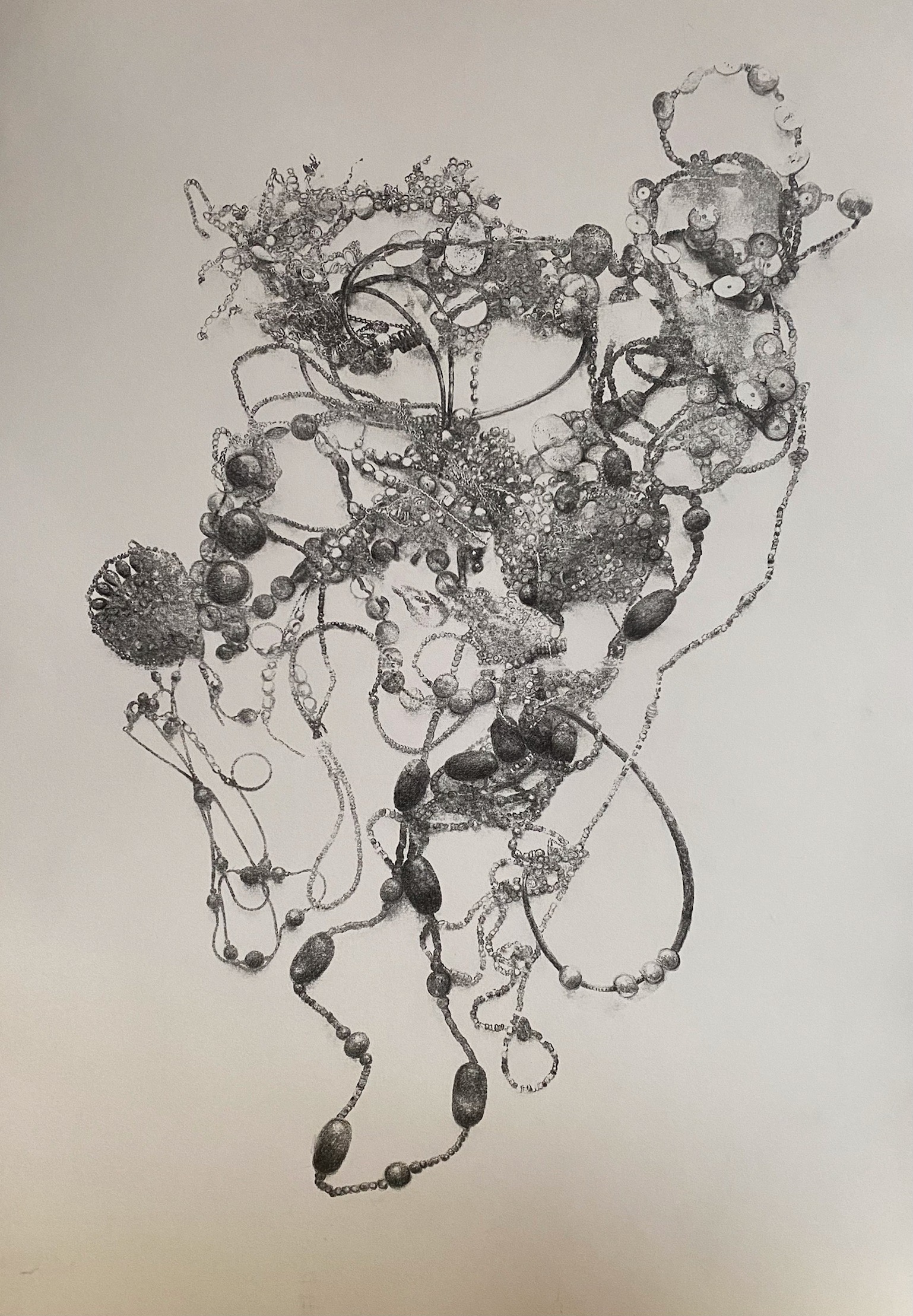

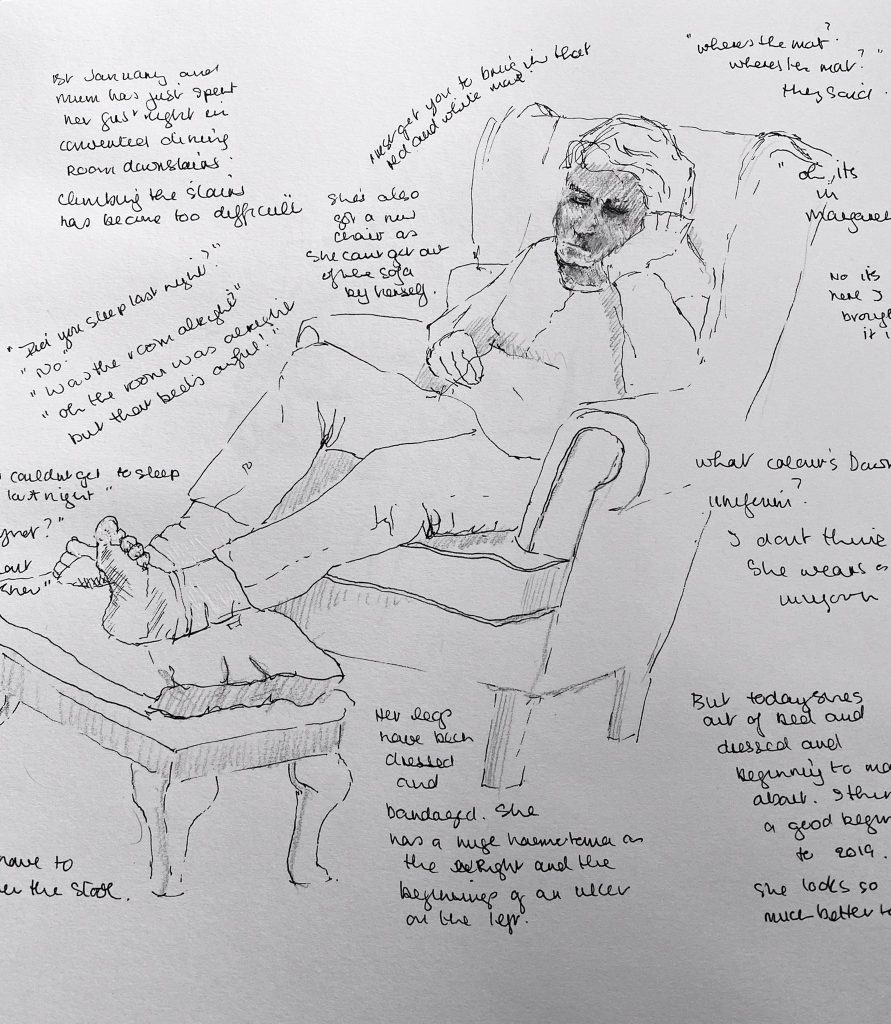

I was grateful that I did have one release and that was drawing. I drew when I could, and I drew my mum. In the difficult moments when she was shouting and yelling, I could sit and draw her, sometimes I even wrote down what she was shouting. Through the repetitive nursery rhymes, the singing, the demons, I drew and wrote as I listened and tried to understand and feel less ineffective and create some calm within myself in the midst of what often seemed like inescapable chaos.

On the good days, it was a lovely opportunity to connect, helping me concentrate on her and her on me. These were special little times that we had. She loved that I drew her, and she loved to see the finished result. In calmer times it initiated a conversation and sparked memories, whereas in the darker hallucinatory days and the loud, loud vocal days it was a way of calming myself and the drawings and the words, merged to make a strange record of our difficult time through this awful illness.

When I eventually looked back on my sketchbook after my mum’s death, I felt the drawings said more about me and my state of mind than about my mum. I had never intended to share these drawings but have been encouraged to do so and they have now become the starting point of an exhibition in Vault Artists Studio’s new Canteen Gallery in Belfast.

I think my mum would have been proud. I think she would love that she was the centre of attention in this exhibition, but I think most of all that she would be so happy that perhaps it might prompt some conversations that need to be had around the focus, understanding and connectivity of care needs for the elderly and their family carers.